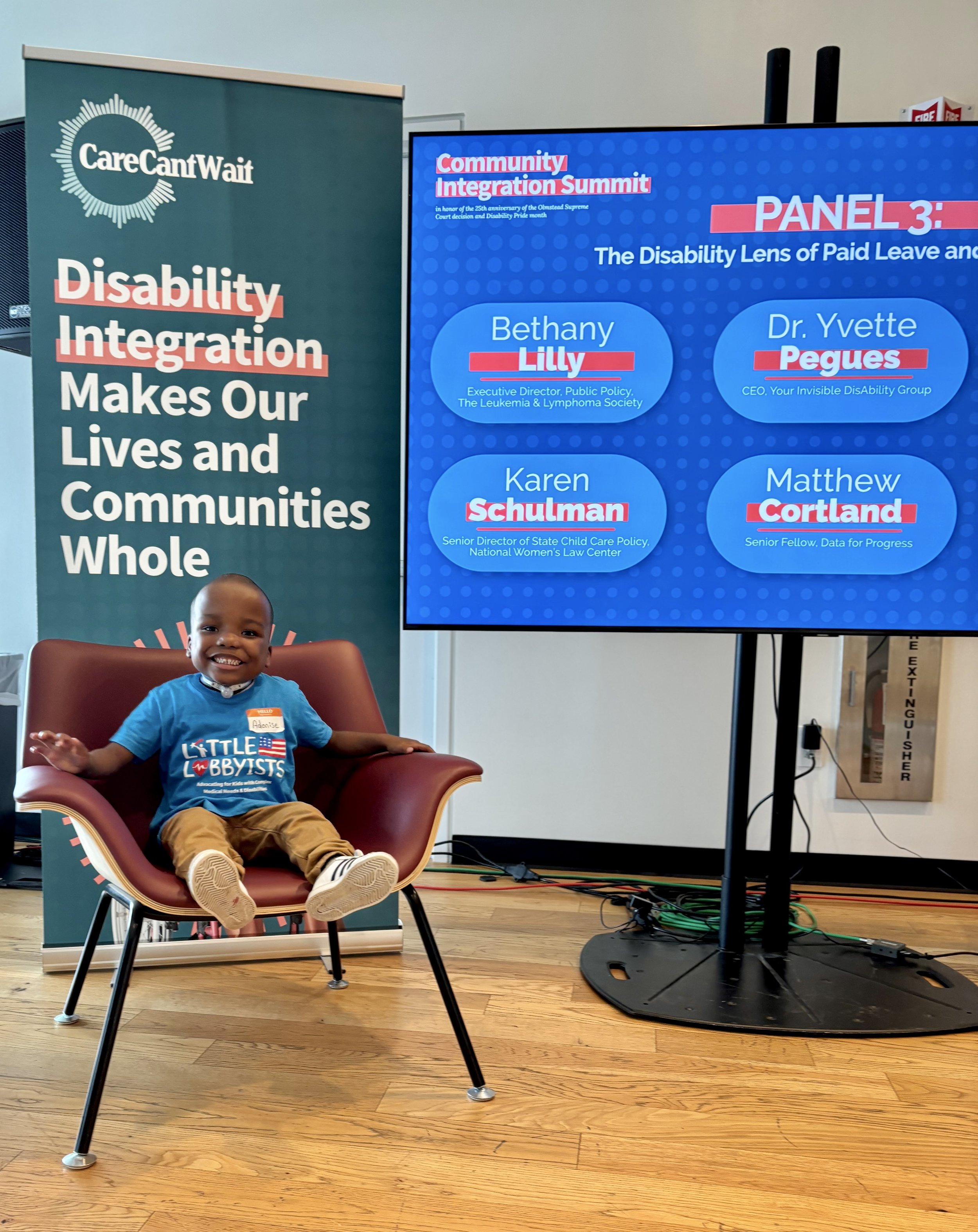

One of our Little Lobbyists, ready to lead a discussion on community! Image description: A young Black boy with a tracheostomy and a big smile wears a Little Lobbyists t-shirt and sits in a meeting room chair in front of a large banner that reads “Disability Integration Makes Our Lives and Communities Whole.” At the top of the banner is the Care Coalition logo, a corona around the words “Care Can’t Wait.” To the right of the boy is an electronic sign displaying the topic of the next panel and the speakers on it.

Did you know that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not ensure civil rights for people with disabilities? The Act “outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin.” The Civil Rights Act does not outlaw discrimination based on disability.

So how then are people with disabilities protected from discrimination and ensured civil rights? It’s complicated, consisting of a set of regulations, a law, and a court decision:

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 protects disabled people from discrimination in any program that receives federal funding, which includes Medicaid, other health services, public education, housing, transportation, and the workforce;

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 protects disabled people from discrimination more broadly, including public settings and situations outside federally funded programs; and

The Supreme Court’s 1999 decision in Olmstead v. Lois Curtis upholds the right of people with disabilities to receive Medicaid services in their communities, if a set of conditions are met.

Disabled people face discrimination on many fronts: jobs, education, housing, physical accessibility, and a variety of health services, among others. However, the key right, the one that unlocks all the others, is the right to community integration. Without the right to live in the community of your choice, people with disabilities would still be locked away in institutions.

What Is the Community Integration Mandate?

The Integration Mandate is the key to civil rights for disabled people. First appearing in the Section 504 regulations, it is codified (established in law) in the ADA. The Olmstead decision upholds it. You can find it in the ADA under Title II, which is based on the 504 regulations that apply to the Department of Health and Human Services. This is the key sentence in the 504 regulations: “A recipient [of federal funds] shall administer a program or activity in the most integrated setting appropriate to the needs of a qualified person with a disability.”

Note that the word “needs” is not restricted; it may apply to medical, social and/or other needs. You can read the entire Integration section of the 504 regulations here.

The Integration Mandate protects the right of people with disabilities to receive their Medicaid benefits in their community of choice. These Medicaid benefits include Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS), which may include medical and rehabilitative services, assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) from home care workers, private duty nursing services (PDN), transportation services, home modifications, and much more.

Why Are Disabled People Still Fighting to Live in Their Communities?

When Medicaid was established in the Social Security Act of 1965, it guaranteed (or entitled) health care services for low-income persons and people with disabilities. However, people with disabilities were only entitled to receive the care many needed in an institutional setting. Nursing homes and Intermediate Care Facilities are institutional settings where disabled people receive care but are kept segregated from the community.

Disability advocates fought long and hard to require Medicaid to provide services in the community. The result is HCBS waivers. The problem with these waivers is that they are still “optional” for states–Medicaid’s “institutional bias” is still part of federal law.

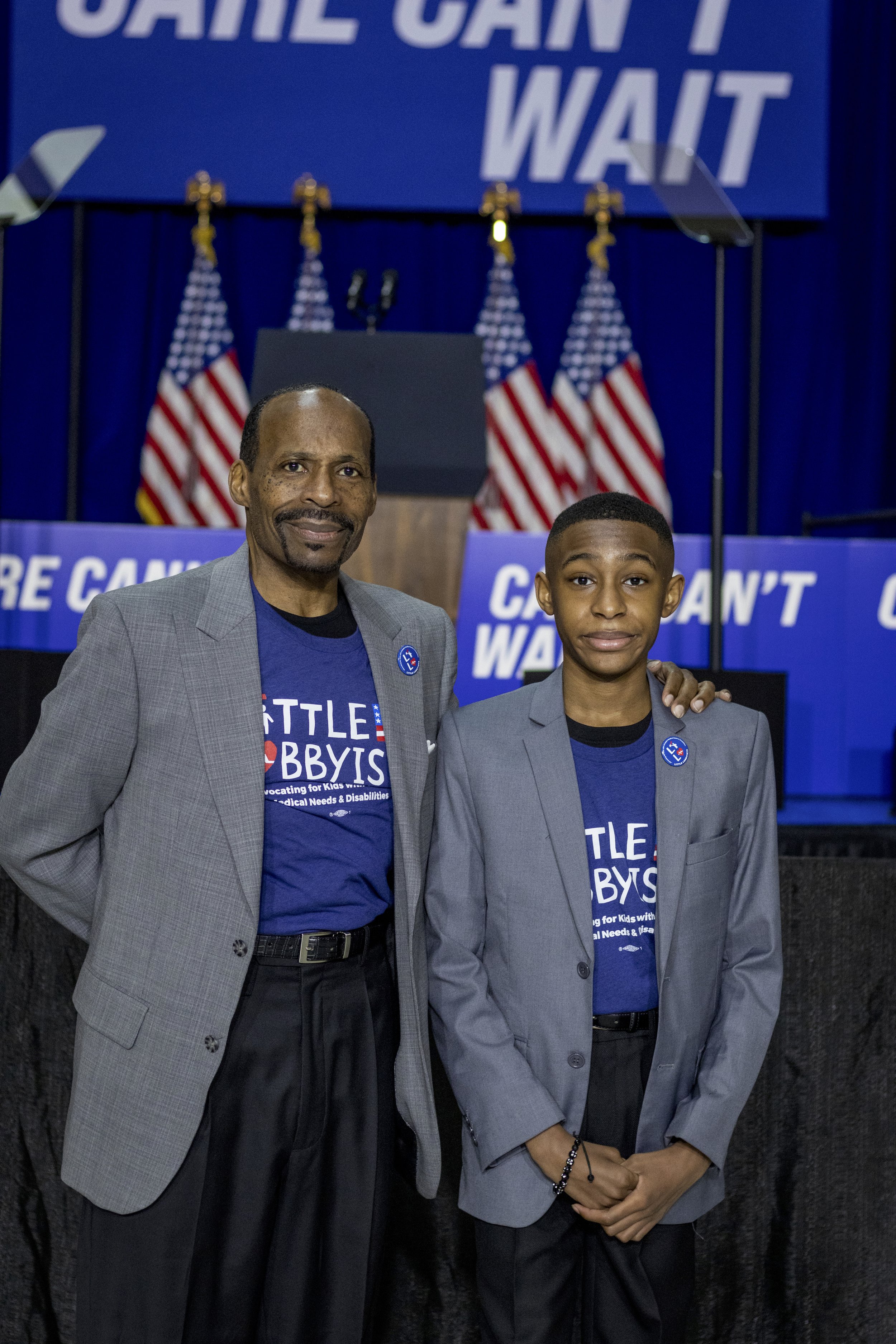

Photo Credit: Rah Studios. Image: Just some of our nationwide Little Lobbyists family at the Care Coalition’s Community Integration Summit in Washington DC! Image description: A couple dozen children of various ages and their parents pose in front of a tan and black paneled wall at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Library in downtown Washington, DC. Most of the group members wear t-shirts with the Little Lobbyists logo.

As a result of ongoing advocacy by the disability community, all 50 states now have HCBS waivers that serve both children and adults, although the terms of each state’s waivers vary tremendously. That’s because Medicaid is a federal/state matching program, and each state is allowed to develop its own terms and conditions:

Type of disability or disabilities served;

Age of the person with disabilities;

Number of slots available for services;

Length of waiting lists for services;

Benefits offered from the allowable list of services maintained by the federal government’s Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

As a result, just because you or your loved one receives HCBS benefits in Massachusetts, it doesn’t mean you understand what others receive in California or why. The sad reality is that what constitutes appropriate “community integration” is still a matter of legal interpretation.

Is There Any Good News?

Yes! As of July 8, 2024, the updated 504 regulations for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services went into effect, thanks to the Biden Administration. Section 504 has not been updated since the late 1970s, when the regulations were first written. As a result, provision of the ADA, Olmstead, and other laws and court decisions have finally been incorporated into the integration mandate, clarifying and strengthening it. You can read the entire 504 Integration section, which describes how states might be violating you or your loved ones’ rights:

Definition of a segregated setting;

What counts as discrimination in the provision of benefits and services by states;

Definition of “risk of institutionalization.”

In addition, the attached guidance to the updated 504 regulations clearly states: “Compliance with Medicaid requirements does not necessarily mean a recipient [e.g., a state] has met the obligations of section 504.” This means that a state cannot claim that because CMS approved their HCBS plan, they are not discriminating against people with disabilities or a subpopulation of disabled people.

If you feel your civil rights have been violated under section 504, you may file a complaint with the Office of Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Secretary of Health, Xavier Becerra, and the Biden Administration are committed to ensuring the civil rights of disabled people.

Jeneva Stone is the blog manager for Little Lobbyists, and mom to Rob Stone.